Treasuries

It all begins with an idea.

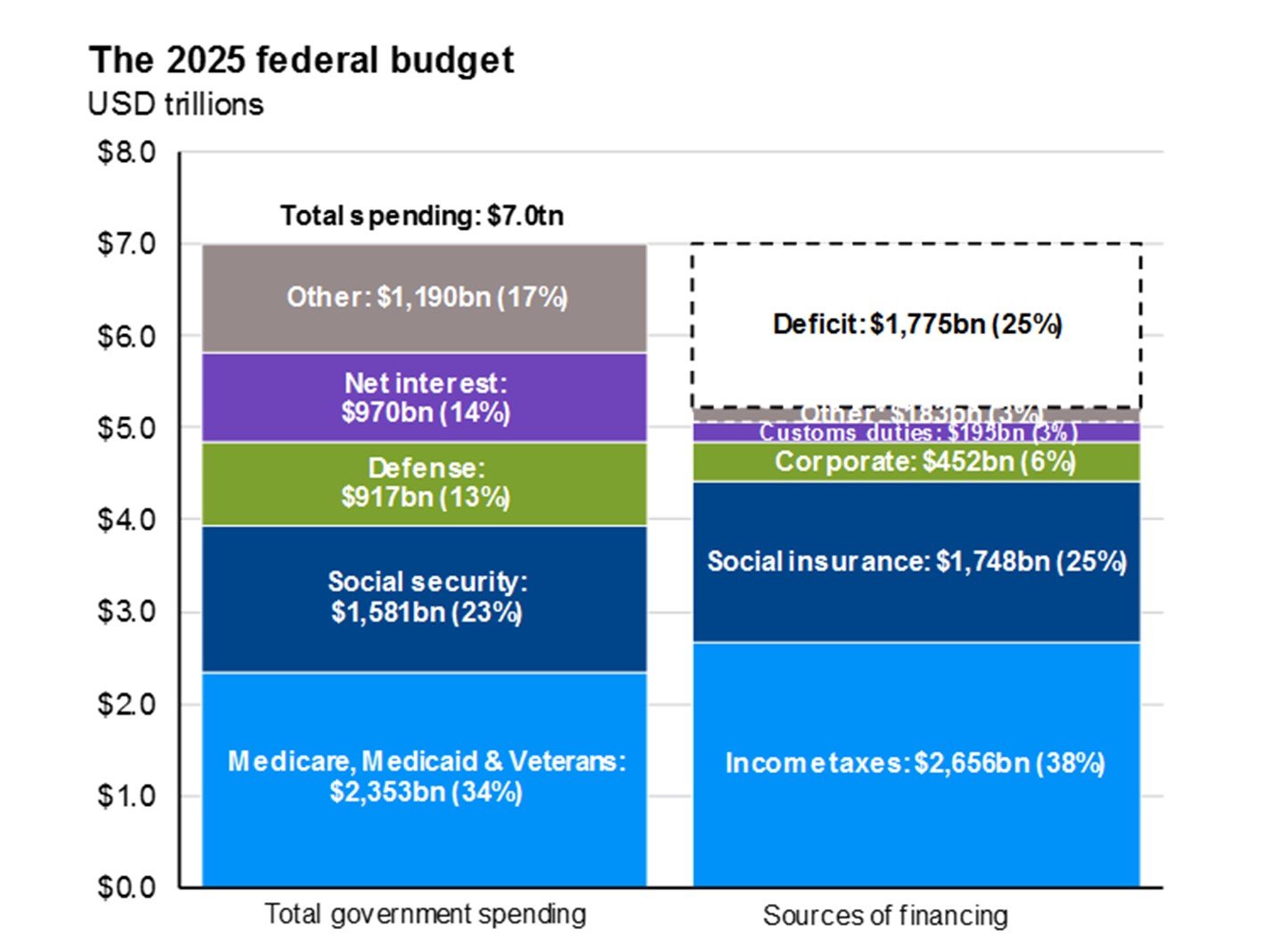

You don’t need a graduate degree in accounting to understand how the federal government’s budget works. In fact, the graphic at the header of the his post makes it pretty simple. It’s from JP Morgan’s “Guide to Markets” and in case you are having trouble reading it, here’s the link:

Guide to the Markets | J.P. Morgan Asset Management

For simplicity I’ll break it down for you. We Spend about $7 Trillion dollars a year. Here’s what we spend it on:

-$1 trillion (970 billion) or 14% on Interest.

-$1 trillion (917 billion) or 13% on Defense

-$1.6 trillion (1.581trillion) or 23% on Social Security

-$2.5 trillion (2.353 trillion) or 34% on (medicare, medicade, and veterans healthcare)

-$1.2 trillion (1.190 trillion) or 17% on “Other”

That’s it in a nutshell. I rounded them a little to keep it simple (as you can see), but that’s what the government spends money on every single year.

The government also makes money, in fact we pull in something in the neighborhood of $5.2 tillion. Here’s what that looks like:

-$2.7 trillion ($2.656 trillion) or 38% on Income Tax

-$1.7 trillion ($1.748 trillion) or 25% on Social Security withholding

-$0.5 Trillion ($452 billion) or 6% in corporate tax

-$200 billion ($195 billion) or 3% in customs duties (NEW!)

-$183 billion in “other”

At first glance, two questions jump off the page for me. One “wow, we’re short $1.775 Trillion dollars every single year?!?” And Two, “what’s going to happen to that “interest” bucket in expenses if we keep running this enormous deficit?”

Let’s table those for a second, because there are some other issues to address. First, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out the “other” column in expenses. “Other” is exactly what is sounds like, it’s everything else. To my republican friends who think we can balance the budget by just cutting some safety nets, or social programs, or literally everything not listed above, you can’t cut it ALL for a number of logistical reasons we hopefully don’t need to explain (planes need to fly, highways need maintenance, etc.). But let’s assume you did cut it all. Everything from the post office to the national parks, no federal reserve bank, no supreme court, all gone… Do that and it’s still going to leave with you with a deficit that’s around $700 billion too wide.

And to my democrat frinds who think we can just raise taxes to fix the problem, you can see the issues there as well. Maybe you’re thinking corporations aren’t paying their fair share? But the US already has a particularly high corporate tax rate among other global economies, and even if you look at just developed economies, we’re still only about the middle of the pact (1). If we raise it much higher companies have an obligation to their shareholders to move their operations overseas. Microsoft is a company designed in Seattle by Americans, where is it based? Ireland, which probably not coincidentally has a very low corporate tax rate. Even if they didn’t move an increase in their tax rate would have a huge and negative impact on their stock prices, stocks owned by a great many Americans in their investing or 401k plans. It would also have an impact on employment, as those companies would have less money to hire workers. But again, for the sake of simplicity, let’s assume you double our corporate tax rate. Ok sweet, we’re still $1.3 trillion short. Want to raise income tax? On who, exactly? Depending on their home States high income earners already pay over 50% tax rates in America. You mathmatically couldn’t double their rates even if they were willing to work for free. Want to start taxing poor people? Good luck winning any election. You could start to creep into Middle class taxes which is where most politicians seem to get pretty creative. But still, you can see there’s not a lot of extra room there either. Let’s assume for hyperbole that you were able to raise taxes on incomes by 50%. Which would absolutely be felt by everyone across the income spectrum (2.656 trillion times 1.5 = 3.984 trillion), you’re still short by about 447 billion.

“Customs” is a bit interesting, and could easily be its own paper (working on it). It’s interesting because it’s new, we’ve never had it as a revenue source. Some argue it’s just a hidden tax (we pay higher prices for goods, so importers can pay the government for it’s tariffs), and some argue it’s a great way to make other countries pay their “fair share”. I’m more of a math guy than a politics guy, so for now let’s table that debate, and instead focus on its percentage, which is extremely small. You’d have to raise them 10x to cover the deficit, and as I hinted to above, doing so would have tremendous ripple effects that I plan to cover in a later paper.

So where does all this leave us? It leaves us with a deficit that’s growing, and that pesky “interest” column will continue to ensure that it grows exponentially, making the imbalance dramatically worse over a very short time period. In fact, if we currently owe 38 trillion ish (2) and we’re adding about 2 trillion every year by way of the deficit, that interest bucket alone will be 50 billion dollars more next year just from interest (3). And that’s some back of the envelope math with you can’t really use because rates are higher not lower as they’re refinancing their securities. The point I’m trying to make is that this problem is getting dramatically worse every year. And will continue to do so until we can stop the bleeding and balance the budget. And balancing it will take more than political blaming from either side, and it will likely require a lot of really tough decisions. Either cutting social security (as elderly people’s lives are getting more expensive), or the military (as the world is clearly not getting any safer), or Medicare, Medicaid, and veterans benefits (which by the way has been where a lot of the recent cuts have been focused, to no avail). Or on the revenue side, we’d likely need to see considerable tax hikes which would have a severe impact on the economy. Likely leading to layoffs, and less personal income for American’s from higher taxes. Switching to my opinion here, because I don’t think there is a solution.

——————————-

I think instead what you’ll see, is a deficit that continues to grow. No one wants to elect the “let’s tighten our belts” president, so they’ll continue to spend and blame. Financing the growing Debt by issuing more and more treasuries. Like all markets, when you overweight supply, you have an equal inverse relationship with demand. As demand for the debt goes down, they’ll continue to raise rates to make them more attractive, paying those rates will make the problem harder and harder until our debt goes the way of all debt and we have to default on it.

From there a couple things will likely happen. Either the deficit snaps close instantly making a lot of these tough decisions for us, and likely not in the direction that we want them to be made. Social security checks won’t get mailed out, military troops won’t get paid, millions of Americans won’t get the healthcare they need. And whoever stops getting paid our interest, will likely not be happy. The vast majority of which are American’s themselves. Other pension funds, investment companies, insurance companies, and even the federal government itself. All will stop getting their interest payments. This will cause our ability to finance debt in the future to deteriorate further, making it much harder for us to grow going forward.

The second thing that will happen is the thing I’m much more curious about. You see we use the treasury rates for a lot in finance. In fact, it’s called the “risk free” rate because of how safe it was always perceived to be. When you try to determine valuations of a fixed income instrument, it’s very common to use the difference between the “risk-free” rate (treasuries) and whatever else you’re measuring. This “spread” is very useful for determining valuations. If high yield corporate bonds are historically 4% above treasuries (spread) what happens when they stay the same price but treasuries rates become unreliable? If you demand a higher interest rate on treasuries, would you then demand a higher rate on all bonds? Or would you prefer to own a bond from say “Apple” or “Microsoft” because it’s perceived as “safer” than treasuries.

An even more important question to ask is “how do I protect my portfolio against this problem?” The first issue is that while the situation is bleak, it’s not a 100% chance that the government doesn’t figure this out. Maybe they do the combination of rasing taxes and cutting spending gradually. Maybe they find a new isolated group that is under taxed, like space travel, or a new type of farming, similar to what happened when the budget was briefly balanced in the 90’s from all extra internet growth/tax revenue. Maybe large groups of the elderly are thinned out by another pandemic or maybe an alien comes to earth with pockets full of gold, who knows? Point is that no matter how probable a default is, it’s not a guarantee. The other much more likely issue is that they could just inflate the problem away. If you owe everyone 38 trillion dollars, why not make a dollar worth half as much, now you basically only owe 19 trillion. It’s not a great solution, it would have tremendously negative implications for the economy, but way less severe than a global default of the world’s reserve currency. Again, there are some exit ramps, which from an investment standpoint, makes it a little harder to handicap.

The other issue is that even if we know WHAT will happen, we don’t exactly know WHEN it will happen. If this happens in 40 years, who cares? Even if it happens in 4 years, what will the return be that we lose out on while we’re hiding in our bomb shelters? The key is to find hedges that a) still perform ok in all of our exit ramp situations, b) aren’t time dependent, because we don’t know the time this would occur, and c) most importantly, would survive the financial armageddon that would ensue from a treasury default. Let’s start by ruling investments out, treasuries are the first to scratch off the list. If they’re what is potentially going to default, they’re definitely out (obvi). What about stocks? They’d probably do ok, right? Keep in mind that most major recessions are caused not by equity bubbles, but by credit bubbles. And 38 trillion dollars (or whatever it is by then) is going to have a gargantuan effect on most assets. And equities which are backed by companies earnings would of course not be immune. Unemployment would spike, GDP would fall dramatically, companies wouldn’t have anyone to sell anything too. I’d imagine they’d have a huge selloff.

What about other bonds? Maybe Microsoft or Apple or some super safe company? Well, the largest “corporate” bond fund in America is Vanguards intermediate corporate bond fund (Ticker:VCIT) which ironically does still own some treasuries in it (4), and even if it didn’t, the spread problem still exists from above. We have no idea how the market would view other debt if the world’s “safest” debt does go bankrupt. Also, in the inflation problem, this could get pretty ugly pretty quickly. No one cares about a nice safe 5% yield from Apple if inflation is at 9% (hypothetically). So I think we can rule out most debt, which the exception of private credit with floating rates. But even then, the rates would have to be backed by companies that can stomach large increases (as their rate floats) in their debt servicing costs. Which is a very small list of companies. I think we can rule this out in a hyperinflation world also.

Ok, what about Crypto Currency? That’s an interesting one. Maybe we just all switch to a new currency, maybe bitcoin replaces the dollar? It’s possible, but there’s zero evidence to suggest we’d all just abandon the US dollar in favor of some digital algorithms. Also, who knows which currency we’d switch to? Bitcoin is the biggest, but others are better at transaction efficiency, or have lower volatility. Or maybe the government adapts their own digital currency and outlaws bitcoin. You can see how choosing the wrong crypto currency would be calamitous in this untested environment. Not to mention, if 38 trillion dollars is sucked out of the economy, I can’t imagine that wouldn’t have an effect on the digital asset that does nothing.

Ok, so what’s left? In my opinion not much. I think real assets are your best bet. Find things that are finite and in heavy demand regardless of market disturbances. People need power, so I like infrastructure. People need to eat, so I like farming, and also commodities. Computer chips still need gallium and houses need copper, and all the other wonderful things we pull out of the ground that have supply controlled by their scarcity. The problem is that commodities are hard to buy. In fact, most commodity funds hold futures contracts (a piece of paper that says you can guy x commodity at y time for z price) and futures contracts are back by cash held somewhere. Now follow me here, but I have a billion dollars worth of commodity futures, that’s usually backed by cash I have somewhere worth considerable less than a billion (margin accounts) and in most cases, that “cash” is held in, wait for it, treasuries…. Dang, they got us again. SO a smarter play would be to own stock in Miners. Own the companies that pull safe needed things out of the ground. It’s not a perfect solution, but in a world where we can’t depend on treasuries to keep the financial peace, I think they’re the best house on a bad block.

Do I think you should run away from treasuries today? No. But I think you need to start increasing the weight in your portfolio to things that are less susceptible to a problem we can see coming from a mile away. Buy infrastructure, buy miners, buy farmland. You can hold your exposure to stocks, since we don’t know when (or if) the treasury default will show up, and you’d likely miss a lot of Equity appreciation if you leave too early. But start to draw down your exposure to treasuries as soon as you can. Even if they don’t default, they’re becoming less attractive by the day. And any problem being managed by politicians will always blow up the same way… eventually.

———

(1) https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/global/corporate-tax-rates-by-country-2024/

(2) https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/americas-finance-guide/national-debt/

(3) 970,000,000,000/38,000,000,000,000=0.0255 add the 2 trillion to 38,000,000,000,000 = 40 trillion. Keep the same rate of 2.55% on 40 trillion is 40,000,000,000,000*0.0255=1.02×10¹² or 1,020,000,000,000 - 970,000,000,000=5×10¹⁰ or 50,000,000,000.

(4) https://advisors.vanguard.com/investments/products/vcit/vanguard-intermediate-term-corporate-bond-etf?cmpgn=FAS:PS:XX:LF:20250101:GG:DM:LB~FAS_VN~GG_KC~BD_PR~LF_UN~FixedIncomeProduct_MT~Broad_AT~None_EX~None:None:NONE:NONE:KW:IntermediateTermCorporateBondETF&gclsrc=aw.ds&gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=21752162092&gbraid=0AAAAADyd_RXR1xUmEpDgYOQeHZFYwcrkB&gclid=Cj0KCQiAjJTKBhCjARIsAIMC449NOTAwobF7ie9280MzvfgbBfGcOnBALH0D5rWhUYXPi7PR4yt1bKcaAuOVEALw_wcB#overview

Bitcoin

It all begins with an idea.

“A cynic is a man who knows the price of everything, and the value of nothing.” -Oscar Wilde

I’ll never forget 2008. It was the worst market I’d ever seen, and I hope that never changes. The speed of the sell off was so quick, it felt like a new company went bankrupt every day. And every time we thought it found a floor, it fell further. Unemployment rates around the globe spiked, even the impenetrable money market funds we’re showing cracks in their foundations... I remember standing in front of a Citibank with my paycheck, just staring at the ATM and wondering if I should deposit that check there, because I wasn’t sure it (or any bank) would be around in the near future. There was a fear in the pit of my stomach that i’ll never forget. It felt like the end of the financial system as we knew it.

People were questioning whether diversification made sense, they were questioning every fee they paid, they were even questioning investing in general. And it was logical to do so; if you invested in the S&P in 1998, and held ten years to the crash of 2008, you lost about 26.5% (1). To add insult to injury, most Americans largest store of wealth has always been their houses. And this recession came for those prices with a vengeance. House prices slumped 30-35% in most markets, Phoenix fell 50%, and Las Vegas was down close to 60%! Nothing made any sense anymore. Years later it became a running joke that everyone told fish stories about how well they held up in 2008. But I’m here to tell you, everyone managing assets was terrified. And with the exception of a few very intelligent hedge funds, everyone lost money.

Like a white knight, in rides Warren Buffet. The model of prudent investing had been stockpiling cash for years prior to the crash. As the buildings were burning he came in buying up all the wreckage he could, and he got fire sale prices. Be bailed out Goldman Sachs, he bailed out Wells Fargo, he told his boards what to do, he consulted the President, even the Federal Reserve. I remember being so astonished by his conviction. Not only did he know to de-risk his portfolios BEFORE the crash, he now seemed so confident to step back into the fray.

The reason for his conviction was not his brilliance, or his patience. Though both are legendary. No, he was so confident because he is a man who understands valuations. And while it may sound simple, determining what something is “worth” isn’t always an easy question to answer. The most basic answer is “whatever someone ELSE is willing to pay for it.” But that’s misleading, if only one person overpays for something, who will they sell it to? If there’s ten of an identical item in a store, and the store clerk cons someone into paying triple for one of the ten, has he changed the value of the other 9?

Fortunately as with most financial vehicles, we can plug in some pretty useful equations, to help us understand a securities value. You can use these numbers to compare it to itself and its peers, over time. One common metric is called “Price-to-Earnings” ratio. It’s exactly as simple as it sounds. You take a stocks price per share, and divide it by its earnings per share. So if Goldman Sachs is currently trading at $854.56 and its earnings per share are $49.22 (for each share you own, the company gives you $49.22 of its earnings) then your P/E Ratio is 17.362. So today, the price you pay per share is 17.4 times the earnings. What if they come up with some insane new derivatives equation, or trading software that grows their earnings exponentially? Now assume they’re earning $854.56 a share. If the stock price stayed the same, you’d have a P/E of 1. Clearly you can see why you’d want that number to be lower. You get more earnings for the price you’re paying. What if their EPS went to 854.56 like the example before, but this time their same ratio held true? The expected stock price would be $14,869.34 (6).

It may seem complicated at first glance, but it’s very simple equations like this that Buffet used to gauge whether he was getting a good value or a bad one, for what he was buying. He was unloading stocks and raising cash when the P/E’s were high, and when he came in to buy everything he could, most of them held single digit P/E ratios. They call him the “Oracle of Omaha” implying he can see the future, but all he really sees is value. You buy a company to get its earnings, if a bunch of stocks gave you one twentieth of their stock’s price in earnings yesterday, and one fifth of your stock’s price in earnings today, you should buy a lot today. Ok, well cool story, but what the hell does any of that have to do with crypto currencies??? And that’s where I need to switch to opinion.

————————

I have a very hard time when I meet people (and I know a good amount), who have Buffett level conviction with crypto currencies. Not because I think they’re right or wrong, but because I have such a hard time determining valuations of crypto currencies. In contrast to the example above, buying bitcoin doesn’t entitle you to their “earnings.” There’s no company, even. So what exactly is it?

Crypto currency at its very base form is a math equation. I’m dramatically oversimplifying, but let’s say I have one bitcoin and I want to give it to you. I send you the pieces of the math problem that establishes I own the bitcoin, a bitcoin miner then checks the equation and he or she approves the transaction, they get a kickback for checking our work, the equation then grows to include the information that you now own it. Again, I’m speaking hyperbolically to illustrate my point, but when it starts it may be 1+1=2. I give you my bitcoin, the miner looks at the equation and says “yup, 1+1=2” and adds a few more numbers showing he checked our work, and some data that the coin now belongs to you. So the equation becomes 1+1=2+8=10. Then you trade it to someone else and the equation is now: 1+1=2+8=10/3+15=18.333. We’re two transactions in, and the equation has already gotten much more complicated than where it started. But that’s it, that’s crypto in a nutshell.

It was designed to be a currency, and frankly it’s pretty brilliant in that. Math equations transcend boarders, they’re free from the busy hands of politicians, there’s no foreign currencies to worry about. If the question you’re asking is, “does the world have a demand for a digital currency that can do all the things that I just said bitcoin does?” The answer would be a resounding “yes!” But the CFA defines an effective currency as being able to do three things. 1) it must be a medium of exchange. Meaning if has to be widely accepted by users in transactions. Beaver pelts for example aren’t “widely accepted” for exchange, so they would not qualify. Most places take US Dollars however, so they would qualify. 2) it must be a unit of account. Meaning it must be widely understood what its value is. People aren’t going to let you use bitcoin to by a pizza today, if that same bitcoin is worth either half a pizza or two pizzas tomorrow. And you’re likely not going to use it to buy a pizza today if you can use that same bitcoin to buy 80,000 pizzas next week. Lastly 3) it must be a store of value. Meaning people can save it, and not have their purchasing power decrease over time.

So where does bitcoin rank in those 3? I’d maybe give it a C- letter grade. Is it a medium of exchange? Sort of, some places accept it. But you can’t walk into a Safeway and use it to buy groceries. And companies that have tried to use it as a currency have reversed course on that decision pretty quickly. As an example, in 2021 Tesla accepted bitcoin as payment for a few months, ultimately reversing course because of “climate concerns” according to the article cited in footnotes (5), but it’s likely no coincidence that the swings in value while they held it were wild and unpredictable. That said, places still do use it for exchange, specifically overseas transactions, or for less reputable sites like gambling, or rocket launcher purchases, or whatever. 2) Is it a unit of account? Not really. Everyone likes to talk about bitcoin’s unprecedented growth, but very few people got in on the ground floor. Most people bought somewhere in the last 7 years after its astronomical growth in 2017 (over 1300%), and since then it’s been extremely volatile. At one point in 2018 its standard deviation was 100%, that’s not investing, that's playing roulette. You had an equal chance you’d lose your whole investment, or double it. Since then it’s came down to around 50% but that’s still very high. Around five times as volatile as stocks, and around 3.6 times as volatile as gold(4).

Volatility may make you lots of money when you’re right, but because of the asymmetry of returns (2), it’s a losing game in the long run. Look no further than 2025, as of the writing of this, it’s down 31.8% YTD (it takes me a few days to write these posts, I’ve had to double that number since I started). I guess you could argue that you usually “know” its value, and that value is “agreed upon”. Thus making it a unit of account. But that’s a bit of a stretch, no one knows its price at all times. And its price swings dramatically even at night, or on the weekends. And 3) is it a store of value? Depends when you ask. Not this year, but to be fair the same could be said to a much lesser extent for the dollar. So again, kind of? The central issue here is that its volatility makes it very hard to work with. Assume you have to pay for something in bitcoin, and you have the exact amount in your wallet, but you have to pay for the item in two weeks, how confident are you that you’ll be able to make the transaction? I think this is a “no”.

So where does this leave us on bitcoin being a currency? Is it a) widely accepted (not really) b) universally understood (sort of) and c) stable price. (No). Lastly, let’s touch on the “climate concerns” Tesla cited in the brief window they were using it. He’s referring to the exponential growth of these equations we talked about before. When bitcoin started, “mining” those equations was relatively easy. The computer power was low, and the power draw for mining was minimal. A billion transactions later, those equations are a mile long and those power draws are immense. Bitcoin now requires more power than the entire country of Poland, or Argentina. In fact, it’s estimated that half a percent of ALL the power used on planet earth, goes to bitcoin mining (3). And that pill gets harder to swallow by the day. If you’re planning to use this for billions of more transactions in the future, how will it handle that power draw? Bitcoin’s proponents argue that computing power will rise to meet the needs, and that may be true. But it also may not be. How can you know for sure without knowing the exact (or even approximate) amount of bitcoins needing to be mined? Whether they’re right or wrong doesn’t change the fact that, it’s a complete guess. But it’s an integral part of this problem. So we have to deal with the information we have today, and it doesn’t look very scalable. At least not with today’s technology.

So if it’s not a currency, what is it? Is it a speculative asset, like gold? I can see that argument. The difference is that gold has mechanical uses, electronic applications, even virtue when making jewelry, or medical equipment. It’s also been used as a currency for much longer, and across a wider group of people. What’s the “need” for bitcoin? It doesn’t really “do” anything. It has value because people think it has value. And fortunes have certainly been made from far less. But from an investment standpoint, there’s really nothing else there. Even if you were to make the argument that it IS a currency, and there’s definitely a demand for that. You’d have to keep in mind that it’s far from alone in pursuing that endeavor. There are literally thousands of other crypto currencies, many of which claim to have solutions to the “climate concerns” issue. Before you tell me about its “first mover advantage” in the crypto market, keep in mind that that’s a fickle mistress in tech, just ask MySpace.

Which brings us back to Mr. Buffett. How do you buy something if you can’t determine its value? How do you know the price you’re paying - for whatever this is - is a good one? Just “hoping” other people continue to think this math equation has value is not an investment strategy, no matter how long that’s worked in the recent past. Not only is Warren a genius at finding what something is worth over the long term, he’s a staunch opponent of bitcoin. His famous analogy was “if you owned all the farmland or apartments in the world, you’d be a trillionaire. If you owned all the bitcoin in the world, its value would drop to nothing and you’d have zero net worth because bitcoin doesn’t do anything.” (7). And I’d assume he has a better grasp on this than the bagger at the grocery store, or whoever told you it’s a great investment.

In closing, while I think there’s a huge demand for a digital currency in application, there’s too much risk in selecting just one. Especially one that’s had such an insane appreciating, and is a ticking time bomb from a power consumption standpoint. For the sake of brevity we haven’t even mentioned regulatory risk (this administration has done everything it can to help crypto, that may not always be the case), technology risk (maybe something better comes along), or security risks (hacking or fraud). The issue in selecting an asset that has had such a meteoric rise, is that you’re more vulnerable to all those unknown risks. Just as Buffett didn’t know what risks were on the horizon when he was selling stocks in 2005 and 2006, he was selling because their inflated valuations made them vulnerable. My target price for bitcoin is significantly below where it’s at now. At least until (or if) you see some price stabilization and some solutions to its exponential power draw, thus improving its efficacy as an actual “currency.” Because whatever is it now, I’m not interested.

————-

(1) On December 31st of 1998 the S&P500 close was 1229.23-December 31st 2008 the close was 903.25=325.98 & 325.98/1229.23=0.265

(2) “asymmetry of returns” is a term used to illustrate that losses have an outsized effect on your portfolio return when compared to an equal upside. As an example, if you have $100 and you lose 50% in year one, you now have 50 dollars. Make the same 50% back in year two and you now have 75 dollars. You lost 25% total in two years even though you had the same gain and loss year over year. It’s a term used to explain why lower volatility is better for long term success.

(3) https://buybitcoinworldwide.com/bitcoin-mining-statistics/

(4) https://buybitcoinworldwide.com/bitcoin-mining-statistics/

(5) https://www.bbc.com/news/business-57096305

(6) Formula for P/E Ratio

The formula is simple:

\[ \text{P/E Ratio} = \frac{\text{Price per Share}}{\text{Earnings per Share (EPS)}} \]

Steps to Calculate P/E Ratio

1. **Determine the Price per Share**:

- Find the current market price of the stock. This data can typically be found on financial news websites or stock market platforms.

2. **Calculate Earnings per Share (EPS)**:

- **EPS** can be calculated using the formula:

\[ \text{EPS} = \frac{\text{Net Income} - \text{Dividends on Preferred Stock}}{\text{Average Outstanding Shares}} \]

- Alternatively, EPS figures are often provided in a company’s financial statements or earnings reports.

3. **Plug Values into the Formula**:

- Once you have both the price per share and the EPS, substitute these values into the P/E ratio formula.

### Example Calculation

Let’s say:

- **Price per Share**: $100

- **Earnings per Share (EPS)**: $5

Using the formula:

\[ \text{P/E Ratio} = \frac{100}{5} = 20 \]

### Interpretation

- A P/E ratio of 20 means investors are willing to pay $20 for every $1 of earnings.

- **High P/E Ratio**: May indicate that the stock is overvalued or that investors are expecting high growth rates in the future.

- **Low P/E Ratio**: May suggest that the stock is undervalued or that the company is experiencing difficulties.

### Key Takeaways

- The P/E ratio is a fundamental valuation tool used by investors.

- It’s important to compare the P/E ratio of a company to its peers and the industry average for a better analysis.

(7) https://www.cnbc.com/2022/05/02/warren-buffett-wouldnt-spend-25-on-all-of-the-bitcoin-in-the-world.html

Margin Accounts

Past becomes prologue…

You have my apologies if this is remedial. And I suspect to many in the industry, it might be. But I am a firm believer that to effectively communicate anything, you have to start by establishing a solid foundation to build from. Today’s musings revolve around Margin accounts. For those of you not familiar with the tool, they’re a form of borrowing that uses your existing account as collateral. Similar to how a home equity line of credit is credit backed by your home; margin is credit backed by your existing investment accounts. They all vary to some degree, be it borrowing requirements, or rates of interest, but the majority of them are pretty straightforward. The amount you can borrow, is determined by the amount you have.

For the sake of simplicity, let’s assume you have $10,000 in your bank account. You saved it, it’s real money, now you’re wondering what to do with it. You can buy $10k worth of securities (Apple or Microsoft or whatever), then that 10k will fluctuate based on the price of what you bought it at. As an example, today MSFT is trading at $517.81. So with $10,000 you can buy about 19 shares (19 x 517.81 =9,838.39), pretty straight forward so far. But what if you LOVE Microsoft, and you think it’s going to appreciate quickly. You’re all in, but you don’t have enough for even one more share ($10,000 - $9,838.39 = $161.61 < $517.81) so you’re tapped out, right? Wrong, you can use that same account to secure more money. Initial borrowing requirements are usually something in the neighborhood of 50%. So you can call any trading platform and say “hey I’d like to open a margin account” and poof, you now have another 20k in your account. It’s not yours, it’s a loan, but it looks and spends like cash. So now you have the ability to buy another 20k in MSFT which would give you a total of 57 shares ($20,000/$517.81 = 38.624 or 38 whole shares, plus the original 19 shares = 57).

So now you have $10,000 real dollars and you have a paper position of 57 shares in Microsoft which as of now equals $29,515.17 (57 * 517.81 =29,515.17). What could go wrong? Well, assuming the price appreciates, nothing. If markets continue to grow there’s no issue. When MSFT hits say 800 dollars a share, You now have the same $10,000 real money, but a whopping $45,600 (57 * 800 =45,600) in unrealized gains, what I’m referring to as “paper money”. If things move in that direction you’re unstoppable. You’ll continue to compound indefinitely. You just made $16,085 (45,600 - 29,515 =16,085). MSFT is up 54.5% (800 - 517.81 =282.19 & 282.19 / 517.81 =0.545) but your 10k investment is now worth $26,085. Keep in mind, if you sell and close out the position you’d likely want to return the 20k you borrowed, but that means if you sell today, you could sell that position and walk away with a whopping 260% (26,085 / 10000 =2.609) off a stock that appreciated 54.5%. What could go wrong?

The flip side of that coin is the issue. If say MSFT goes to $400, you now have the same 10k but only $22,800 (57 shares * $400= $22,800). Even though you only have 10k skin in the game, you lost 7000 dollars! In this hypothetical, MSFT lost 22.8% (517.81 - 400 =117.81 & 117.81 / 517.81 =0.228) but your account is now worth $2,800 ($22,800- your borrowed 20k) meaning you lost 7,200 in real money from your original 10k or a -72% (7200/10000=0.72) return.

What’s worse is that you are now likely below your margin requirement, and you would likely need to meet a “maintenance margin.” Maintenance margin is a number that you always have to stay above. Usually, it’s something below initial margin requirements, for the sake of this example let’s ballpark 25%, as it’s the most common. So, you need 10k to borrow 20k, giving you 30k to invest in totality initially, but if your account were to dip to 22,800 in the hypothetical above you now have $2,800 in real money and the same $20,000 in borrowed money. Meaning you’re below your margin requirement (22,800 - 20,000 =2,800 & 2,800/22,800=0.123 so 12.3% < 25%). This is going to trigger a lot of bad stuff, likely someone will reach out and tell you that you have to deposit more money to get your account above the “maintenance level”, or they’ll forcefully sell your shares for you to meet it themselves. You start to see why Mark Twain quipped “a banker lends you their umbrella when the sun is shining but wants it back the second it starts to rain.”

——

Ok, thanks for all the math, but what’s the point? The point is that major market dislocations typically happen when borrowing disappears. In 2008 the market to borrow money for houses evaporated when owners of houses could no longer make their monthly payments. They couldn’t do this because many of their rates floated significantly higher than they had ever planned for, pushing their monthly payment amounts above what they should have qualified for, but let’s table the specifics for the sake of this parallel. If people don’t want to buy your loan, banks don’t want to issue it. You (and everyone else) can’t get loans, house prices go down. Because house prices don’t care if you bought houses on credit or with cash, it all appreciates their prices the same. When that credit you used to drive up prices disappears, prices adjust downward. Similarly, the Great Depression was caused by these exact margin accounts hitting support levels forcing people to liquidate their positions. MSFT likely appreciated when you (and everyone like you) used 20k of borrowed money to buy it. It’s not real money for you, but the appreciation in the price of the stock is very real, the reverse is unfortunately also true.

As of September 2025 margin levels in retail trading accounts are in the neighborhood of $1.13 trillion, according to FINRA. That’s a staggeringly large number. To put that in perspective, if you were to buy every company in the S&P 500 at the same time (assuming prices didn’t move) it would be about 60 trillion dollars. What’s even more perplexing is that the vast majority of 2025’s stock market gains are in a very small group of names dubbed “the magnificent 7” or Apple, Microsoft, google, Amazon, Nvidia, Facebook, and Tesla. Added together those stocks alone account for about 21 trillion (#1 in footnotes).

You probably have two questions. First, if the total S&P index comprised of 500 companies is $60 trillion, how is it that just 7 of those 500 companies account for over a 3rd of that number? And second, what happens if that $1.1 trillion in margin gets taken away, or “called” as in the example above? To be perfectly honest, no one knows. The federal reserve is an exponentially different player than ever. And global markets, crypto currencies, and the AI booms have all created very unique market valuations. It becomes clear that investing “Art” isn’t always investing “science”.

We can use history to help us find at least a little perspective. In 1929 the total market cap of the S&P was something like $300 billion total. Admittedly we need to do some ballpark estimates here, because of how markets have evolved over the last 100 years. It was basically the S&P 90 back then (the actual S&P 500 wasn’t launched until 1957). But of that $300 billion, there were estimated to be around $9 billion in margin accounts. As for concentration, the top 7 companies then accounted for only about $18 billion (#2 in footnotes). Back of the envelope math is pretty interesting in itself. In 1929 the market was worth $300 billion, and margin (paper money) accounted for about 9 billion of that. So of the $300 billion about 3% was “credit” (9/300=0.03).

From a crude comparison we look ok, so far. Margin was 3% of the total benchmark in 1929, and only 1.8% (1.1/60=0.0183) today. Sweet, plenty of room to run, even if we adjust for rounding and my watered down math. But I think the story here is the combination of credit, AND the dramatic difference in concentration. Back then the top 7 companies only accounted for about 18 billion of the 300 billion total. That means the top 7 companies accounted for 6% (18/300=0.06) of the broader benchmark. Today the top 7 companies account for 35% (21 trillion / 60 trillion).

In his new book “1929” Andrew Ross Sorkin does a remarkable job humanizing the crash. He tells stories of characters from president Hoover to J.P. Morgan, even some comedians of the time like Charlie Chaplin and Groucho Marx. After losing a tremendous amount of money in US Steel (market cap at the time - $4 billion) Mr. Marx is quoted as telling his advisor “my biggest mistake was in trusting you.” What I found somewhat chilling was when he discussed RCA. At that time it had a market cap of around $1.5 billion, an extreme valuation that the author describes advisors justifying to clients as being worth the valuations because of a tremendous new technology (radio) that they were bringing to the market.

I’ll let you decide how correlated Nvidia’s AI, and RCA’s radio are, to their respective broader economies. That’s a whole different essay in and of itself. My main argument is that if the top 7 of 90 companies accounting for 6% of the total market where able to dislocate margin accounts totaling 3% of the market, what can 7 of 500 companies accounting for 35% of the broader market do to margin accounts totaling 1.8% of the market?

The answer is of course that no one knows. Markets are much larger now, the federal reserve is much more involved, even margin limits themselves are significantly different than they were then. My concern is in the fragility associated with that level of concentration. If the market was 60 trillion spread evenly across 500 companies, each company would only account for $120 billion (60/500=0.12). In that hypothetical, assume Apple gets hacked, has some unfavorable tariff change their business, or even something we can’t imagine like their headquarters gets hit by a meteor, we’d be down a very survivable 120 billion in a 60 trillion dollar market. Today however if the same black swan event happened it would send a 4 trillion dollar shockwave across markets forcing margin accounts to come up with cash they don’t have. And when they can’t product it, their securities would be forcibly sold and further exacerbated the drawdown.

Again, for the sake of this post, I don’t claim to know what specific risks are lurking around the moats of these companies. Instead I just want to point out how fragile this type of leverage makes an economy. And more importantly I want to call your attention to how this particular credit instrument can (and has) topple even the strongest of markets. Especially when risk is concentrated largely across 7 companies instead of the perceived 500. Please invest accordingly.

——-

#1. As of early November 2025, the market capitalizations of the Magnificent Seven stocks are approximately as follows:

1. **Apple Inc. (AAPL)**: $4.0 trillion

2. **Microsoft Corporation (MSFT)**: $3.85 trillion

3. **Alphabet Inc. (GOOGL)**: $3.3 trillion

4. **Amazon.com Inc. (AMZN)**: $2.62 trillion

5. **NVIDIA Corporation (NVDA)**: $4.53 trillion

6. **Meta Platforms, Inc. (META)**: Approximately $1.63 trillion

7. **Tesla, Inc. (TSLA)**: Approximately $1.46 trillion

#2. Top Companies and Their Estimated Market Caps in 1929

1. **U.S. Steel Corporation**: Approximately **$4 billion**

2. **General Electric**: Approximately **$3.5 billion**

3. **Standard Oil of New Jersey**: Approximately **$3 billion**

4. **AT&T (American Telephone and Telegraph)**: Approximately **$2.5 billion**

5. **General Motors**: Approximately **$2 billion**

6. **Chrysler Corporation**: Approximately **$1.5 billion**

7. **Railroad companies (such as Pennsylvania Railroad)**: Approximately **$1.5 billion**